Can We Predict Human Behaviour? A Discussion With Brett Hall

He says no, I say yes.

A breakthrough can become a trap, if it is used uncritically, repetitively, limitlessly.

- Edward Said, Traveling Theory

A blog exchange with Brett Hall.

Background and Setup

(VM: See Brett’s pre-written response here, uploaded four hours after this post went live. I will let readers decide if that counts as an “exchange” or not.)

Brett Hall is an excellent scientific communicator and expositor of David Deutsch’s ideas, and a fellow connoisseur of hard-hitting criticisms. He’s someone with whom I agree on 90% of the important issues, and two weeks ago we had a good natured twitter disagreement exploring that remaining 10%. We both decided it was meaty enough to warrant a full length blog post exchange, and by mutual agreement I’ve volunteered to kick things off.

For the impoverished few of you who may not be familiar with Hall’s work, definitely start with his podcast TokCast (where “ToK” stands for “Theory of Knowledge”), which is largely dedicated to bringing David Deutsch’s ideas to a wider audience, and is a great secondary resource to consult if you’re just diving into Deutsch’s work for the first time. He has an associated YouTube channel which contain digestible short videos which complement the podcast, and a blog which explores different topics than those he covers on his podcast. I’ll be sure to link to his response here when it appears.

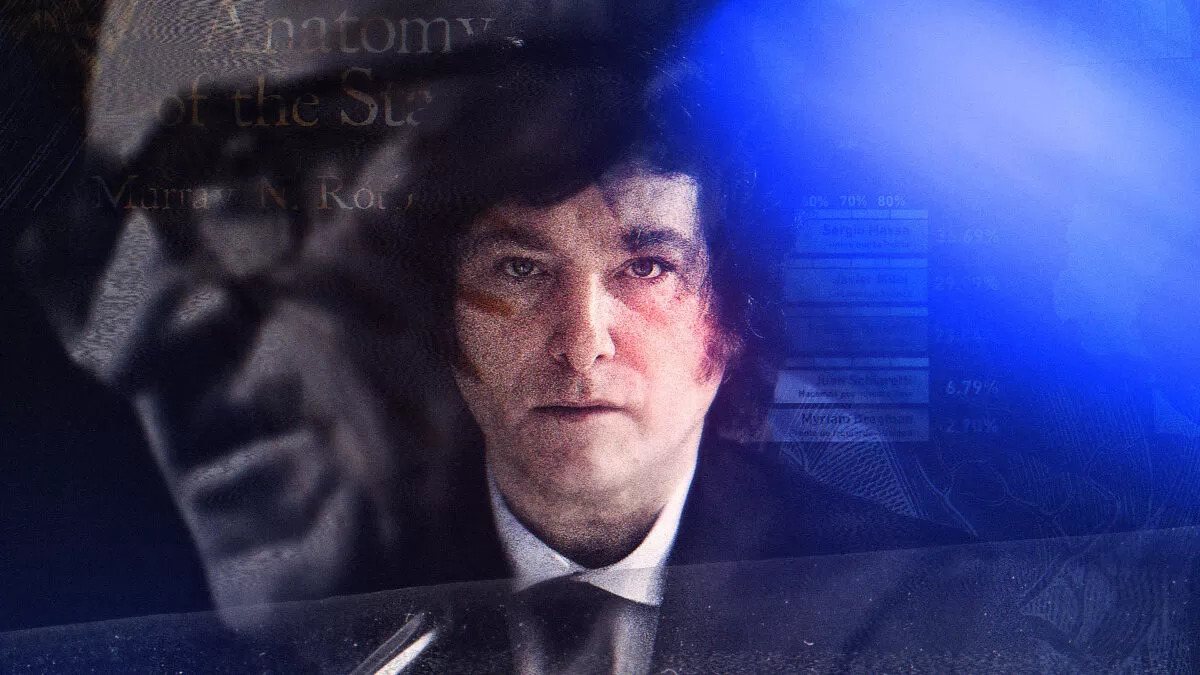

Who the heck is Javier Gerardo Milei?

Recently, I proposed a simple test which, if passed, would convince me of the validity of Austrian Economics (AE). Shortly afterwards, Argentina proposed an even better one. On November 19, 2023, Javier Gerardo Milei, an avowed Austrian, was elected into office with a sweeping 55.7% of the vote, the largest win since Argentina’s new democratic era began. So if economic outcomes in Argentina improve over the next four years, this would be a fairly convincing case for AE.

Milei is … an interesting fellow. He liked his first dog Conan so much, for instance, after Conan died he cloned five brand new Conans - one named Conan, whom he considers to be literally exactly the same as the original Conan, as well as the Conans’ identical twins, Murray, Milton, Robert, and Lucas. He also communicates telepathically with Conan, Conan, Murray, Milton, Robert, and Lucas to get advice on politics, economics, and foreign policy.

Note I’m using google translate for quotes here and elsewhere.

He is a practicing tantric sex instructor who is superhumanly capable of “remaining three months without ejaculating” (“In tantra, anyone who takes less than 45 minutes is considered a premature ejaculator”, Milei added helpfully, for comparison). On the same radio show, he announced to his majority-catholic electorate that he has participated in several threesomes, 90% of which, he clarified, were the good kind. He never combs his hair, has a superhero persona named “General AnCap”, and when asked about his stance on the sale of children, he was quick to reassure parents that

If I had a child, I wouldn’t sell them, but that’s not the current topic of discussion in Argentine society. Maybe it will be in 200 years, I don’t know.

Besides these achievements, he also has a bachelors degree in economics from the University of Belgrano, two master’s degrees from the Institute for Economic and Social Development and Torcuato di Tella University, respectively, and has been a professor for over 21 years teaching macroeconomics, microeconomics, growth economics, and mathematics for economists. He has published 9 books, over 50 academic articles, and nearly 100 journal articles, and is a member of both the World Economic Forum, where he serves as chief head, and B-20, the economic policy group of the International Chamber of Commerce. He has also recently been presented with an honorary doctorate and the title of visiting professor by the Escuela Superior de Economía y Administración de Empresas.

And on December 10th, this Austrian Economist / successful politician / accomplished academic / telepathic non-ejaculator will become the 58th President of Argentina1.

~

So I genuinely don’t know what to think of the man. But he sure is planning some sweeping political reforms, which presents us with a great opportunity to learn about the effects of certain policy choices.

According to Wikipedia, notable proposed policy changes Milei plans to implement include:

- Abolishing the Central Bank of Argentina, which he described as “one of the greatest thieves in the history of mankind.”

- Legalizing the sale of human organs, and concurrent with the above policy, deregulating the legal market for weapons.

- “Government spending cuts so large that austerity measures demanded by the International Monetary Fund would look ‘tiny’ in comparison”.

- State prohibition of abortion (note prohibition is the opposite of decriminalization, meaning this policy will require the full force of The State to enforce.)

- Repealing state guarantees on labor rights and pensions, as well as fully dismantling the entire social security system, all of which he describes as “cancer.”

- Privatizing healthcare, education, and roads.

- Either shutting down, privatizing, or redefining Argentina’s National Scientific and Technical Research Council, which “directs and coordinates most of the scientific and technical research done in universities and institutes,” and boasts the status of being the 141st most prestigious research institution worldwide, out of the 8084 total research institutions surveyed.

- Reducing the number of governmental ministries from 18 to 8, including the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Social Development, and the Ministry of Health.

Maybe it’s the Canadian in me, but my instinct here is that all these policy proposals are terrible ideas that will hurt the Argentinian people greatly. But many critical rationalists strongly disagree, and are very gung-ho about the election of Milei into political office. As are 55.7% of Argentinians.

So because he was democratically elected, and because many people I respect are in favor of him and his policies, I’m more than willing to suspend my horror skepticism about most of these proposals (except the abortion one, and the legalize-organ-sales-while-simultaneously-deregulating-guns one, which doesn’t take an econ genius to predict will lead to an increase in gauze, bathtub, and ice cube sales), and wait four years, so we may learn from these natural social experiments by, in Popper’s words, “comparing the results obtained with the results expected.”

Except Brett Hall doesn’t think it’s possible to have “expected results” - i.e make predictions - when we’re dealing with human beings. Which brings us to our disagreement.

The Disagreement Between Brett and Myself

The single most basic and widely understood principle in the Popperian canon is the importance of falsification. If you know anything about Popper, you know about his falsification criterion.

In this spirit, I tweeted out the following:

Do any AE/CR folks want to put falsifiable conditional predictions on the line for what we should expect to see after four years of Milei's government? Important to avoid the Marxist line "Well that wasn't *real* Austrianism" in the case where things go poorly.

— Vaden Masrani (@VadenMasrani) November 20, 2023

To which Brett responded:

Impossibly high standard. Politics/morality don’t consist of testable content in the main. Just as well too! (Or people would be tempted to keep trying to refute communism as you imply).

— Brett Hall (@ToKTeacher) November 20, 2023

Among other things: knowledge creation (making all predictions involving people prophesies).

There were some other messages shared as well, but in this post, I’m going to focus on Brett’s claim that “All predictions involving people [are] prophesies”. The use of the word “prophesy” here is crit-rat2 speak for “completely delusional and impossible”, and is to be contrasted against “predictions” (word used in the standard way), which are legitimate, and play a key role in the scientific enterprise.

There are actually two disagreements at play, since we’re both claiming to be representing Popper’s epistemology accurately.

First: Does Popper in fact say, or does Popperian epistemology imply, that it’s impossible to make predictions about human behaviour?

Second: Can we, in fact, make predictions about human behaviour?

Brett may want to focus on another aspect of our online exchange, and reframe the subject in his follow-up post. Brett, you’re more than welcome to do so, and I’ll follow you into whichever territory you want to venture, but I’ll focus on these two for now.

Because of our first disagreement, I’ll rely as heavily as possible on direct quotes from Popper to argue my position for our second disagreement, which is quite simple: Yes, of course we can make predictions about human behaviour, we do it all the time.3

Here is an example: I predict Brett will either rebut my argument or publicly change his mind, because he’s a critical rationalist, and that’s what critical rationalists do (despite the fact that - hopefully - a wee bit of knowledge will be created in between this post and his.) A second simple example would be supply and demand, which is obviously predictive of human behaviour. Presumably Austrians believe in the laws of supply and demand?4

Conversely, Brett’s position leads immediately to a logical paradox.

What does it actually mean to say prediction is “impossible” in this context? It can’t mean that the human brain literally cannot make predictions, because we make predictions about human behaviour all the time (“I predict my landlord will get upset if I stop paying rent”, for instance).

So might it mean that all predictions will necessarily be wrong? This leads to paradox as follows.

If that was the case that “all predictions will necessarily be wrong”, I would just invert my prediction, so it would be correct again (“I now predict my landlord will not get upset if I stop paying rent”). But according to the claim, this new prediction would also be wrong, so I’d flip it back again… and again, and again, as I tumble headfirst into an infinite regress.

This is a formal proof by contradiction (the vicious kind), which shows that some predictions of human behaviour are possible, although we of course won’t know which predictions those are, until we actually make them and check. In Our Theory is Metaphysical, not Scientific, we provide examples of the class of predictions to which Poppers result applies, and the class of predictions to which it doesn’t. Arguments for why predicting human behaviour must be possible, and how we actually go about making them in practice, are embedded within the list of responses to common objections below.

And I’ll end this post with a direct challenge to Brett, to be addressed in his followup post. But before that, we need to anticipate us some counterarguments, to which we now turn.

Common Objections

You hear a lot of misunderstandings and over-applications of Popper online these days, so let’s go through the list. Here, I list out a number of common crit-rat objections to making predictions (never thought I’d see the day …), and responses to each. It’s designed to be skimmable, so each section is relatively self-contained, and written such that the reader can skip to sections of higher interest. The topics we’ll cover are:

- Our Theory is Metaphysical, not Scientific.

- We’re Interested in Explanations, not Predictions.

- Because of Logic: Empiricism / Inductivism / Ought-is

- The Oedipus Effect: Predicting Changes the Predicted

However, if I’m asking my opponents to state in advance what will change their mind about AE, it seems only fair if I do the same.

So before diving into each objection, in the spirit of incrementalism, let me write down, for the record, a number of indicators which, if they trend in positive directions after four years, would completely change my mind about Austrianism. So much so that I’ll be legitimately curious as to how the heck the Austrians did it, and why all the other mainstream economists (even libertarian leaning ones like Tyler Cowen, Russ Roberts, and Deirdre McCloskey) so obviously missed why the unorthodox policy choices listed above were the right call after all. And I’ll dedicate a few posts, plus pods with Ben, to exploring the details of the Austrian method publicly, so I can better understand what about AE allowed Milei to be so successful, and will work to help our listeners and readers understand as well.

Using data from Our World In Data where available (or equally credible sources), these indicators are:

Many thanks to Ben Chugg for these help with indicators.

- An increase in GDP per capita, total factor productivity (typically considered a marker of technological progress and production efficiency), or the growth rate of the median income.

- A decrease in inflation (or perhaps more realistically, a decrease in the rate of inflation)

- An increase in various measures of development, such as: the human development index, average education levels, democratic capital, or the security of property rights and legal structure

- Repayment of some of its debt to the IMF, or increased participation in the world economy (via, e.g., forming new or bolstering existing trade agreements).

Austrians, however, are opposed in principle to “theories attempting to explain the economy via aggregates.”5. Does this mean that if the GPD per capita, say, of Argentina goes down after four years of Milei’s government, Austrians would consider that meaningless? When I posed this question to an Austrian friend of mine, the answer was yes, yes they would. Further, s/he reiterated that

[Austrians] explain in general why [indicators like the above] are meaningless (how [they] can go up and still be bad or go down and be good). In the case of Argentina they’ll try to understand what really went on.

So no matter what the conceivable outcome of Milei’s government is, Austrian Economics will have an explanation for it. Their explanation is so good, it can always fit the data. And fortunately for them, their theory also tells them they don’t have to make any “risky” predictions either - that is, predictions which could potentially put their theory at risk.

Which brings us to our first objection.

Our Theory is Metaphysical, not Scientific.

My theory is metaphysical, not scientific, and thus can’t make predictions and can’t be subjected to empirical tests.6

This one uses a bit of insider-lingo, so let’s take a step back, and explain what Popper means by “metaphysical” in this context.

The year was 1919, summertime. Popper was sixteen, and sometime around his birthday, as teenage boys do, he was thinking about Marxism, Freudianism and Adlerianism. In particular, he was thinking about how enamored many of his friends were with the great explanatory power of these particular -isms. Conjectures and Refutations (C&R), p.64:

I found that those of my friends who were admirers of Marx, Freud, and Adler, were impressed by a number of points common to these theories, and especially by their apparent explanatory power. These theories appeared to be able to explain practically everything that happened within the fields to which they referred.

- C&R, p. 45

The problem with these -isms, Popper noticed, was that with these types of theories,

“Manifest” means “obvious”.

Whatever happened always confirmed it. Thus its truth appeared manifest; and unbelievers were clearly people who did not want to see the manifest truth; who refused to see it, either because it was against their class interest, or because of their repressions which were still ‘un-analysed’ and crying out for treatment.

- C&R, p. 45

That meant that whatever the possible outcome, be it an outcome now, or four years after an election, no matter what happens, it would demonstrate that the -ism was correct.

Popper provides two examples, one from Freud and the other from Adler:

I may illustrate this by two very different examples of human behaviour: that of a man who pushes a child into the water with the intention of drowning it; and that of a man who sacrifices his life in an attempt to save the child. Each of these two cases can be explained with equal ease in Freudian and in Adlerian terms. According to Freud the first man suffered from repression (say, of some component of his Oedipus complex), while the second man had achieved sublimation. According to Adler the first man suffered from feelings of inferiority (producing perhaps the need to prove to himself that he dared to commit some crime), and so did the second man (whose need was to prove to himself that he dared to rescue the child).

- C&R, p. 46

And it was precisely the fact that these -isms had so much explanatory power, which made them so attractive to Popper’s friends:

It was precisely this fact — that they always fitted, that they were always confirmed — which in the eyes of their admirers constituted the strongest argument in favour of these theories. It began to dawn on me that this apparent strength was in fact their weakness.

- C&R, p. 46-47

By contrast, Popper also considered Einstein’s Special and General Theory of Relatively, which of course aren’t -isms. In particular, he was impressed with Einstein’s willingness to make a risky prediction:

With Einstein’s theory the situation was strikingly different. Take one typical instance — Einstein’s prediction, just then confirmed by the findings of Eddington’s expedition …

Now the impressive thing about this case is the risk involved in a prediction of this kind. If observation shows that the predicted effect is definitely absent, then the theory is simply refuted. The theory is incompatible with certain possible results of observation — in fact with results which everybody before Einstein would have expected. This is quite different from the situation I have previously described.

- C&R, p. 46-47 (italics in original, emph. added)

So now we are finally in a good position to understand what Popper means by “metaphysical theories’’. He distinguished between Marxism/Adlerianism/Freudianism, on the one hand, which he referred to as “metaphysical theories”, from Einstein’s theories on the other, which he referred to as “scientific”7:

I thus felt that if a theory is found to be non-scientific, or ‘metaphysical’ (as we might say), it is not thereby found to be unimportant, or insignificant, or ‘meaningless’, or ‘nonsensical’. But it cannot claim to be backed by empirical evidence in the scientific sense.

Of course, Popper anticipated that new -isms, with extraordinarily high explanatory power, would continue to reappear in the future, and so he undertook a close study of the differences between Einstein and the -isms. He documented his findings into a list of seven conclusions (C&R, p.47-48), where the third conclusion also happens to be the basis of Deutsch’s constructor theory.

I’ve included the full list in a footnote below8, but here want to focus only on conclusion 3) and 4), as these will allow us to better understand what Popper means when he speaks of “metaphysical” theories:

3) Every ‘good’ scientific theory is a prohibition: it forbids certain things to happen. The more a theory forbids, the better it is.

4) A theory which is not refutable by any conceivable event is non-scientific. Irrefutability is not a virtue of a theory (as people often think) but a vice.

When people say “my preferred theory X is metaphysical, and thus can’t make predictions”, or “my theory is only descriptive, not prescriptive”, or “my theory describes things as they are, not as they should be” or “you can’t get an ought from an is” (discussed further below) as a means of getting out of making predictions, they are failing to realize that this is the very thing Popper is objecting to, which lead him call these theories ‘metaphysical’ in the first place.

Instead, they choose to focus on the fact that Popper has also written that metaphysical theories still can have merit, sometimes. Yes, they can, sometimes. But make no mistake, Popper absolutely considered irrefutability a flaw, a weakness, a deficiency to be rectified.

There is a clear hierarchy here. As bullets 3 and 4 unambiguously state, theories which make predictions are better, and theories which don’t are worse. This is why Deutsch has worked so hard to make the Many World Interpretation falsifiable, and why he is currently working to make constructor theory falsifiable as well. Because he recognizes that physics has a strong tradition of not “taking seriously” theories which don’t make risky predictions - which is why, for example, string theory hasn’t taken off. But unlike the disheartened string theorists, who have thrown up their arms in despair after decades of noble failed efforts, proponents of Austrianism instead fold their arms, and refuse to try.

As we will see in a moment, economists make risky predictions all the time. If Austrianism is unable or unwilling to make predictions, Austrianism isn’t ready to play with the big boys yet. The time spent by Austrians on Twitter justifying why their theory doesn’t need to make predictions, would be time better spent trying to fix their theory such that it can.

~

Fortunately, there are many serious Austrian scholars who are doing just that.9 One such person is Javier Gerardo Milei, the incumbent president of Argentina.

In his paper Monetary Essays for Open Economies: The Argentine Case, he provides an example of a conditional risky prediction that meets the criterion I laid out in my initial tweet:

Thus, if when the CEPO opens, if there were not an extremely strong confidence shock that would increase the demand for money (M1) and this would contract towards the good equilibrium (8.5% of GDP), the inflation rate would climb to levels of 150%, while in the case bad (3.8% of GDP) the inflation rate could be around 450%. In this context, the level of activity could fall between 3% and 6% and poverty would exceed 50% of the population.

- JG Milei, Monetary Essays for Open Economies: The Argentine Case, p.17

And as it turns out, despite their apparent differences, Professor Javier Gerardo Milei shares a very important similarity with Oxford’s Nick Bostrom, the AI Doomers, and the Longtermist communities as well, because they all believe in an impending technological singularity.

From the abstract of his paper From the Flintstones to the Jetsons, Wonders of Technological Progress with Convergence:

These describe how the convergence and acceleration of growth based on human capital and technological progress will put us in front of an economic singularity where economics would cease to be the science of managing scarcity and become the science of the study of human action in an environment of radical abundance.

- JG Milei, From the Flintstones to the Jetsons, Wonders of Technological Progress with Convergence (emph. added)

Perhaps the Austrians should tell this Austrian he’s using Austrianism incorrectly? And that he has a lot of shared research interests with Bostrom and Kurzweil? And also that, while it’s super great that he’s planning all those sweeping societal changes listed above, it’s extremely important he doesn’t use his theory to make predictions about what the consequences of his policies will be? Viva la revolución.

~

Also, a brief aside. Recall that Brett is arguing that Popper has proven that, given the growth of knowledge, predicting human behaviour is impossible. The proof he’s referring to comes from the preface of The Poverty of Historicism (PoH), the book Popper wrote alongside Open Society and its Enemies as his part of his “war effort.” I’ve discussed this result extensively before, and would note here only that step three of Popper’s proof explicitly does not refer to all predictions made about human beings, and is only referring to predictions made “about the future course of human history”.

For instance, an example of predicting “the future course of human history” would be Milei’s prediction of an impending technological singularity coming sometime in the future, where importantly, the date is not specified. Milei’s other forecast, regarding future inflation rates given that the CEPO opens, would be an example of a conditional prediction, because it states that “if such and such happens, in this time window, we expect such and such to happen.” These kinds of predictions are completely fine, because they are about specific events occurring under specific conditions at specific times, after which we can verify whether or not the conditions were met, and the prediction successful.

And yes, it is the case that in some instances, the act of prediction, or of knowledge growth more generally, changes the very thing predicted. And this certainly makes prediction under these changing circumstances more difficult. But fortunately, we have techniques to handle this, discussed in detail below.

We’re Interested in Explanations, not Predictions.

Prediction actually plays a very small role in science. What is more important than prediction is explanation, and we have a great one. We’re interested in explanations, not predictions, so it doesn’t really matter if we can or will make predictions with our theory.6

This is a common refrain one often hears. We are interested in explanations, not predictions, the story goes. This objection can be dealt with rather easily, because as Popper explains, once you have a theory in hand, there is no significant difference been using that theory for explanatory, predictive, or testing purposes - it just depends on one’s particular interests. PoH, p.103 - 107

The use of a theory for predicting some specific event is just another aspect of its use for explaining such an event. And since we test a theory by comparing the events predicted with those actually observed, our analysis also shows how theories can be tested. Whether we use a theory for the purpose of explanation, of prediction, or of testing, depends upon our interest; it depends upon the question which statements we consider as given or unproblematic, and which statements we consider to stand in need of further criticism, and of testing.

…

What is important is to realize that in science we are always concerned with explanations, predictions, and tests, and that the method of testing hypotheses is always the same (see the foregoing section). From the hypothesis to be tested — for example, a universal law — together with some other statements which for this purpose are not considered as problematic — for example, some initial conditions — we deduce some prognosis. We then confront this prognosis, whenever possible, with the results of experimental or other observations. Agreement with them is taken as corroboration of the hypothesis, though not as final proof; clear disagreement is considered as refutation or falsification.

…

According to this analysis, there is no great difference between explanation, prediction and testing. The difference is not one of logical structure, but rather one of emphasis; it depends on what we consider to be our problem and what we do not so consider.

- If it is not our problem to find a prognosis, while we take it to be our problem to find the initial conditions or some of the universal laws (or both) from which we may deduce a given ‘prognosis’, then we are looking for an explanation (and the given ‘prognosis’ becomes our ‘explicandum’).

- If we consider the laws and initial conditions as given (rather than as to be found) and use them merely for deducing the prognosis, in order to get thereby some new information, then we are trying to make a prediction. (This is a case in which we apply our scientific results.)

- And if we consider one of the premises, i.e. either a universal law or an initial condition, as problematic, and the prognosis as something to be compared with the results of experience, then we speak of a test of the problematic premise.

- PoH, p.103 - 107

(italics in orig, emphasis added, spaced out for readability)

So to summarize. Once we have a theory, we can use it for three purposes - explanation, prediction, testing - and these depend on the particular problem we’re trying to solve. To make this concrete, let’s use a simple toy example.

Your car won’t start, and so you entertain a few theories/hypotheses as to why. You consider two theories in particular - the first is that the car won’t start due to broken spark plugs, and the second is it won’t start due to it being out of gas. Each of these theories can be used either for explaining, predicting, or testing, as follows:

-

Explanation: Here, as Popper says, our problem is not to “find a prognosis”, but rather, to “find the initial conditions or some of the universal laws (or both) from which we may deduce a given ‘prognosis’. In the context of Popper’s philosophy, a “prognosis” is the predicted outcome derived from a theory, when applied to a specific set of initial conditions.

In the car example, we might say “If my car won’t start due to a broken spark plugs, the ‘initial conditions’ would be that the gas tank isn’t empty, the spark plug is malfunctioning, and the rest of the parts of the car are working as intended.”

To use the ‘spark plug theory’ for explanatory purposes in this context would simply mean that our problem is to answer the “why” question: “Why would broken spark plugs lead to the car not working?” The explanation would involve the inner workings of a car (or “laws of automobiles”), what spark plugs are used for, and why a car wouldn’t start if spark plugs are broken. Similarly, using the “gasoline” theory would result in a different explanation, which instead would focus on the role gasoline plays in combustion engines.

-

Prediction: If we wish to use our theory not for explanation, but for prediction, we would instead consider the laws and initial conditions as given, and deduce new information, that is, a predicted outcome.

Here it might be something like “Assuming the car won’t start due to malfunctioning spark plugs, and given the explanation of how cars work, we deduce that turning the ignition key will result in clicking sounds”. Similar predictions could be made from the “gasoline” theory as well.

-

Testing: In this setting, the problem under consideration is that one or more of our assumptions about the initial conditions of the car might be erroneous (“should we assume the spark plugs are broken, or that gasoline is missing?”). Hence we’re interested in testing our theory, by comparing “results obtained to results expected”. “Oh, hmm, I don’t hear a clicking sound when I turn the engine. This must mean my assumption about broken spark plugs was incorrect.”

So we see that, in Popper’s words, “there is no great difference between explanation, prediction, and tests” - they simply depend on what it is we’re trying to use our theory for.

~

Why is this relevant? Because Brett Hall doesn’t think it’s possible to have “expected results” - i.e predictions - when we’re dealing with human beings. And because of the equivalence between prediction, explanation, and testing Popper discusses above, his view therefore implies that it’s not possible to have explanations when we’re dealing with human beings either.

But it’s even worse than this. As we have seen, all experiments rely on predictions10. If Brett believes it’s impossible to make predictions about human behaviour, he believes - contra Popper - it’s not possible to experimentally test the effects of any policy change whatsoever. Which means Hall is claiming Deutsch was in error when he (Deutsch) endorsed Popper’s criterion in Beginning of Infinity (BoI), Chapter 13, p. 372, which states:

Popper’s criterion: Good political institutions are those that make it as easy as possible to detect whether a ruler or policy is a mistake, and to remove rulers or policies without violence when they are.

If we can’t make predictions, we can’t run experiments. If we can’t run experiments, we can’t detect mistakes. If we can’t detect mistakes, we can’t detect mistaken rulers, or mistaken policies. If Hall’s interpretation of Popper is correct, he has shown that Popper has disproved his own criterion.

And note: It’s no use arguing “but our theory is metaphysical!” here. Chapter 13 of BoI is entirely about voting, which is inherently an empirical, not metaphysical, mode of error correction. Both Popper and Deutsch have empirical falsifications in mind when they speak of “mistakes” in the context of Popper’s criterion, and specifically have the voting mechanism in mind as the empirical (and democratic) means by which we detect mistaken rulers and non-violently remove them from office.

To wit: Hall is implicitly claiming - contra both Popper and Deutsch - that social life is the one arena where we can’t correct errors.

Because of Logic: Empiricism / Inductivism / Ought-is

Using data to make predictions is Empiricism, using history to inform our predictions is Induction, and because of Hume’s Ought-Is dilemma, we can’t get policy recommendations from our theory anyway, or for that matter, predictions about what their outcomes might be.6

Logic is also often used as a justification for why Austrianism can’t make predictions. This comes in three major flavors:

- We can’t make predictions because of Empiricism: If we suggest using data to inform our predictions, we are told by some that this is committing the sin of empiricism, which any good critical rationalist knows was logically refuted by Popper (actually Hume, but nevermind) who showed one cannot derive theories from observations.

- We can’t make predictions because of Induction: If instead, we suggest using historical examples to inform our predictions, we’re told that this is committing the sin of inductivism, because to do so is to “assume that the future will resemble the past”, which again was logically refuted by Popper/Hume.

-

We can’t make predictions because of Hume’s Ought/Is dilemma: Austrians use Hume’s ought-is dilemma, another logical argument, in a slightly different way than the other two. Here, the claim is that because Hume showed you cannot logically derive “ought” statements (which tell you what you ought to do) from factual statements (which tell you what actually is), similarly, you cannot derive policy recommendations from descriptive theories, such as Austrianism.

What this means in practice is that, should Milei’s tenure go catastrophically badly over the next four years, proponents of AE would say this tells us nothing at all about the validity of AE itself, because policy recommendations are not logically entailed from AE. Thus, because of logic, AE is unable to make predictions about which policies will be better than which other policies. And also because of logic, AE is protected against all empirical criticism whatsoever, such as catastrophic policy outcomes.

~

I’m convinced that most of these claims are due to a misunderstanding about the relationship between logic on the one hand, and argument on the other. Exploring the difference between the two which will be the focus of this section.

I want to borrow some text from a previous post of mine to provide intuition about what we mean when we speak of one statement “logically entailing” another statement. To shamefully quote myself (with slight modifications):

But what does “logical entailment” really mean? I like to think of it as an operation which allows us to “move truth around”, from one sentence over to the next. If $x$ “entails” $y$, what we’re saying is, if we’re willing to assume $x$ is true, then we automatically know $y$ is true.

Synonyms or near-synonyms for “logical entailment” you’re likely to encounter are: “logical consequence”, “derived”, “deduced”, “follows from”, “logically valid”, “necessarily true”, “necessary truth”, “thus”, “logical conclusion”, “therefore”, “hence”, etc.

Let’s see an example of logical entailment in action. Consider a formal disproof of the claim “Austrian Economics is metaphysical, therefore it can’t make predictions”:

Note this is just a pretentious way to prove the obvious - that the existence of Milei’s predictions mean AE isn’t metaphysical.

- Premise: If Austrian Economics is metaphysical (\(M\)), then it cannot make predictions (\(P\)). In logical terms: \(M \rightarrow \neg P\).

- Contrapositive of Premise: From the first statement, we deduce that if Austrian Economics can make predictions, then it is not metaphysical. Logically: \(P \rightarrow \neg M\).

- Assertion: Austrian Economics can make predictions (cf. Milei’s predictions above). This is asserting that \(P\) is true.

- Conclusion: Given the above, Austrian Economics is not metaphysical. If the premise \(M\) is true, then the conclusion \(\neg M\) must also be true, based on the contrapositive relation established in step 2. QED.

Like with Popper’s proof (the guts of which are contained within The Open Universe: An Argument for Indeterminism), this is a proof by contradiction, although unlike Popper’s proof, mine is bone-head simple.

That is, by starting from an assumption (Austrianism is metaphysical, therefore it can’t make predictions), it is possible to form a chain of logically-entailed statements arriving it’s contradiction. If you accept the validity of one proof, you necessarily accept the validity of the other, because they share the same logical structure.

Now with our intuition about logical entailment in hand, let’s return to the claim that we cannot make predictions because of Empiricism, Induction, and Hume’s Ought-is dilemma.

~

The ought/is thing, for all the trouble it’s caused, is surprisingly easy to clear up. Before reading the Wikipedia article on it, the main thing to realize is that by “get”, Hume is referring to “logical entailment”. The ought/is dilemma is simply saying you can’t “move truth around”, between descriptive statements and normative ones.

That is, in the following example, logical entailment breaks down:

- Premise 1 ($P_1$): The house is on fire

- Premise 2 ($P_2$): There is a child in the house

- Conclusion ($C_1$): Therefore, we ought to save the child from burning to death.

QED.

Hume correctly pointed out that we cannot logically deduce $(P_1 \wedge P_2) \nvdash C_1$, no matter how hot the fire, or young the child.

But logical entailment is a “nice to have”, not a “must have.” Most of the time, logical entailment is either too difficult to show, or your opponents won’t respect it, even if you do show it. So the vast majority of the time, we have to rely on good arguments instead. (Do you, reader, expect each sentence in this post to be logically entailed by the preceding one?)

So instead we ask: Is $C_1$ a good argument with respect to $P_1$ and $P_2$?

Of course it is. Only a complete psycho, or an analytic philosopher, wouldn’t be able to “get” $C_1$ from $P_1$ and $P_2$, if you take “get” to mean what most people mean, which is “have the idea that…”. As in, “Oh, I get it!” Or, “Ah, yes, I get what you mean.” Or, “Oh, I get that the ought-is thing is totally overblown”, etc.

In other words, while the above derivation may not logically hold, what on earth could possibly be wrong with the following argument?

The house is on fire. There is a child in the house.

ThereforeI think we ought to save the child from burning to death.

~

One of the beautiful things about considering explanations as playing a primary role in epistemology is that it relaxes the requirement that every statement must logically entail every other statement - which is why an explanation is not required to be a logical proof.

If relaxing the requirement of logical entailment is valid, as those who accept the primacy of explanations in science are forced to admit, then the entire Ought-Is objection collapses. We “get” policy recommendations from theory the same way we get all our ideas - by conjecture.

And so to with the Induction/Empiricism arguments as well. As I discuss extensively in The Problem of Induction and Machine Learning (Sections I-III), Popper’s critiques were focused on the almost century-long efforts by his fellow philosophers to figure out how to logically entail the logically un-entailable. As Deutsch puts it:

To bridge the logical gap, some inductivists imagine that there is a principle of nature – the ‘principle of induction’ – that makes inductive inferences likely to be true.

- BoI, p.14

All of Popper’s critiques about Induction and Empiricism were exclusively targeted at attempts to “bridge the logical gap” - i.e attempts to logically entail the logically un-entailable.

At no point have Popper or Deutsch ever said we are not justified in using data or history to inform our predictions, only that no amount of historical data can logically entail said predictions. I invite those who disagree with this reading to provide quotations.

Also, if you’re an Austrian who believes you can’t “get” policy proposals from theories, why are you so excited that an Austrian has been elected in office in the first place? According to you, his theory will tell him absolutely nothing at all about what he should do, or which policy to enact. He may as well be a Marxist, or a Keynesian, because in terms of policy ideas, his theory doesn’t matter at all. Heck, he could be getting his policy recommendations telepathically from his dogs for all it matters, if you believe that you can’t “get” policy proposals from descriptive theories.

And finally, for those who are still unconvinced, and think my focusing on logical entailment here is missing the point entirely, here’s a little question for you, phrased in two parts.

1. What did Hume mean by “get”, if not logical entailment?

2. Under this definition, why can’t you “get” an “ought” from an “is”?

Using any non-logical synonym for “get” you like, such as conjecture, argue, guess, think, speculate, reason, abduce, infer, extrapolate etc, please explain, publicly, why we can’t “get” $C_1$ from $P_1$ and $P_2$.

Next question.

The Oedipus Effect: Predicting Changes the Predicted

Unlike in physics, predicting human behaviour changes the very thing we are predicting, making it impossible.6

To this objection, Popper dedicates all of Chapter 25 in PoH, titled The Variability of Experimental Conditions.

Let’s begin with a bunch of examples, which come from an earlier part of the book. Here’s a list of predictions about human behaviour Popper considers valid, phrased in the form of empirically falsifiable prohibitive laws (à la constructor theory):

- You cannot introduce agricultural tariffs and at the same time reduce the cost of living

- You cannot, in an industrial society, organize consumers’ pressure groups as effectively as you can organize certain producers’ pressure groups.

- You cannot have a centrally planned society with a price system that fulfils the main functions of competitive prices.

- You cannot have full employment without inflation.

Another group of examples may be taken from the realm of power politics:

- You cannot introduce a political reform without causing some repercussions which are undesirable from the point of view of the ends aimed at(therefore, look out for them).

- You cannot introduce a political reform without strengthening the opposing forces, to a degree roughly in ratio to the scope of the reform.(This may be said to be the technological corollary of ‘There are always interests connected with the status quo’.)

- You cannot make a revolution without causing a reaction.

- You cannot make a successful revolution if the ruling class is not weakened by internal dissension or defeat in war.

- You cannot give a man power over other men without tempting him to misuse it—a temptation which roughly increases with the amount of power wielded, and which very few are capable of resisting.’

Nothing is here assumed about the strength of the available evidence in favour of these hypotheses whose formulations certainly leave much room for improvement. They are merely examples of the kind of statements which a piecemeal technology may attempt to discuss, and to substantiate.

- PoH, P.52

If we rearrange the words of this objection a bit, we get something nearer to the truth: Predicting human behavioural change is possible, by discovering those behavioural changes which are impossible. This is what gives us our theory, from which we can deduce our predictions.

But Popper actually makes a different point in this chapter. To the claim that “unlike in physics, predicting human behaviour changes the very thing we are predicting, making it impossible”, he replies: This happens in physics too, and yet, the method of experiment is applied all the time.

Because of the rough equivalence between explanations, predictions, and tests discussed above, this objection is equivalent to saying that “we can’t run an experiment without changing the experimental conditions the experiment is run in” (hence the title of Chapter 25). This is called the observer effect in physics, and is completely commonplace.

An example of the observer effect would be measuring the pressure of a tire, which causes some of the air to escape, changing the very thing we are measuring (pressure in this case). Another example would be using photons to observe the position of small particles. To detect the position of the particle, we have to bounce photons off it, which changes the position of the very particle we’re trying to observe.

How do physicists handle the observer effect? Popper provides a careful treatment of this question in this chapter, but here I want to make a different point, and one which is completely compatible with his11. Once physicists have their preferred explanation in hand, they make predictions using statistics, and the probability calculus, because these are the mathematical tools required to deal with varying experimental conditions.

~

It is often said by some in our community that statistics is “explanationless”, and thus completely worthless. But here we see it’s proper role. The proper role of statistics is to complement, not replace, theoretical scientific explanation, by providing tools to aggregate and analyze predictions made under varying experimental conditions.

(Or to put it more sharply - complaining that we can’t handle changing experimental conditions after you’ve dismissed statistics as “worthless”, is like complaining you can’t see after taking your glasses off.)

Statistics is how the famous Eddington experiments were validated, for instance. From NASA:

The original Eddington Eclipse Experiment (for the 29 May 1919 total solar eclipse) was a test of Einstein’s General Relativity, which predicted that the apparent positions of stars near the eclipsed Sun would be shifted outward by up to 1.7”. Their results were from 7 stars on 7 plates, with the measured shift at the solar limb of 1.98 ± 0.12”. On 6 November 1919, Eddington announced the triumph of Einstein, with many far-reaching effects. To further test General Relativity, the basic ‘Eddington eclipse experiment’ was run successfully at six later eclipses (the last in 1973), all with only ~10% accuracy.

See the little “±” and “%” signs? These means the same experiment was run multiple times, and each time, we got different results, which we then aggregated. Statistical aggregation is necessary precisely because experimental conditions change between predictions.

That means we can say two things about Einstein’s general relativity, which is arguably the canonical example of a hard-to-vary explanation, and as we saw in the previous section, the example which inspired the development of critical rationalism itself:

- It “attempts to explain via aggregates” (to borrow a phrase from my anonymous source earlier), because aggregation of experimental predictions is always required when one is dealing with the real world. Conditions always vary between predictions.

- We would not have been able to falsify Newtonian mechanics without statistics and probability. Along with theory, statistics and probability are prerequisites for experimental falsification. Science wouldn’t work without statistics, or explanations. Both are required, and it is their union which makes prediction possible.

Statistics isn’t the same thing as Bayesianism, although some crit-rats seem to treat it like it is. Statistics is how we get around the fact that every time we run an experiment, the experimental conditions change a bit, due to factors outside our control.

This is called “noise” by statisticians. And it doesn’t matter much what causes the noise - be it our own actions, or something else - as long as we have techniques designed to handle it. And we do. It’s the tool physicists have been using since the 18th century. It’s called “statistics”.

Yes, this is all well and good, you say. But what about the use of statistics specifically in regards to predicting human behaviour? To answer this question, and to conclude this post, we turn to the Popperian psychologist Paul E. Meehl, who successfully combined critical rationalism with another famously unfalsifiable -ism: Freudianism.

~

Paul E. Meehl deserves to be much more widely known than he is. Described by Psychology Today as the “Smartest Psychologist of the 20th Century”, he has worked closely with two of Popper’s students, Imre Lakatos (“The only person I’ve ever worked with who had people shot.”) and Paul Feyerabend (“Drunk two-hundred martinis with him all told over the years, in the old temple bar.”), as well as B.F. Skinner (“Spent hundreds of hours arguing with him and had a great time at it.”)12, and Rudolf Carnap (“He would tell people that he was a ‘logician philosopher’, meaning somebody like Hegel was full of baloney”), among many others.

A small sample of a few of his accomplishments I enjoyed:

- His 1954 work Clinical vs. Statistical Prediction: A Theoretical Analysis, where Meehl advocated for an objective, quantitative, and algorithmic approach to clinical psychology, rather than a subjective, Bayesian, “gut feeling” based approach.

-

His excellent polemic Why I Do Not Attend Case Conferences, which criticizes his own field of psychiatry for its lack of a tradition of criticism, thereby trying to create this tradition ex nihilo. He states the reason he doesn’t he attend psychiatry conferences delicately:

The main reason I rarely show up at case conferences is easily stated: The intellectual level is so low that I find them boring, sometimes even offensive,

before providing a highly detailed, itemized 14 point list of common deficiencies he’s noticed in his colleagues’ thinking (“If you want to shake people up, you have to raise a little hell”).

- His concept of the Nomological Network gives us an entirely new way to think about, and mentally visualize, the nature and structure of objective knowledge via the evocative metaphor of a living, growing network.

- His paper Theoretical Risks and Tabular Asterisks: Sir Karl, Sir Ronald, and the Slow Progress of Soft Psychology opens with a savage line about theories in the field of psychology, saying most are “neither refuted nor corroborated, but instead merely fade away as people lose interest”, before providing a list of 20 problems in psychology, many of which are still relevant today. He then reiterates (one of) Popper critiques of Bayesianism, before focusing his attack on the famous frequentist statistician Ronald Fisher, for Fisher’s introduction of the statistical significance test - i.e “p-values” - into psychology, thirty years before the replication crisis began.

All this is to establish his Popperian bona-fides, so that when he goes on to explain just how exactly one can use statistics to make predictions about human psychology (crit-rat trigger words italicized) he won’t be as quickly met with accusations of “prophecy”, “instrumentalism”, “behaviourism”, “positivism”, “explanationlessness”, and the like. He’s well aware of these arguments, too - Deutsch isn’t the only accomplished academic who has built upon Popper’s work, after all.

His discussion of how one goes about predicting human behaviour can be found in his 12-part lecture series13 of his online, titled Philosophical Psychology, which is also filled with delightful personal anecdotes of the various people he’s worked with throughout his career (“It often fills out your cognitive apprehension a bit, to know what someone says while pressed, rather than what they write in their book”)14. I’d encourage those readers who want a deeper analysis into this subject consult Meehl’s lectures.

I want to end this post with Meehl, not because he makes pithy one-liner knock-down argument against Brett’s claim in his series, but rather, because he serves as a positive example of what a serious attempt at grappling with the question of predicting human behaviour actually looks like.

Meehl also serves as another positive example as well: An example of how critical rationalism can successfully mix with other -isms. Rather than torture Popper’s arguments into new ways for Freudians to justify their practice of avoiding making any sort of falsifiable predictions, Meehl recognized that his fondness for Freudianism didn’t exempt it from Popper’s critiques. He then got to work, as with great effort, managed to use Freud’s theory to successful predict that the wall plaques in the stairwell of the Washington Monument would show more financial donations from fire departments than police departments.

Whether or not he was ultimately successful in his attempts to make Freud’s theory more scientific is certainly up for debate, but besides the point. My point here is only that he tried. And through his efforts, made significant contributions to the field of psychology as a whole, by making it more quantifiable, more rigorous, less subjective, and less Bayesian. And in so doing, provided us with new tools to grow our collective objective knowledge about the inner workings of the subjective human mind.

In other words, he brought the Popperian attitude into Freudianism, rather than the other way around. One hopes the many Austrian crit-rats out in the TwitterVerse may follow his example.

Conclusion

Why would Popper put his famous impossibility result in the preface, one might wonder. If it was as simple as that, what’s the rest of the book for?

The rest of the book is for spelling out, in great, careful, Popperian detail, the background context necessary to understand 1) Why this result is important 2) What all the possible objections to it are, and their rebuttals 3) Where the result applies and where it doesn’t apply, 4) Why it doesn’t contradict Popper’s other writings, and 5) Why it doesn’t say all predictions about human behaviour are impossible.

I’ve included a google drive link to the entire book, so interested readers can confirm this for themselves15. Chapters 19 - 26 in particular are where Popper addresses how we can make predictions about human behaviour. I’ve only briefly sketched out a few of his arguments here, and encourage the reader to read the primary text for a far more comprehensive analysis than what I was able to provide in this post.

It’s unclear to me if Brett has or has not read these sections, but to clarify, it’s totally okay if he hasn’t yet found the time! The dude wrote a lot of books, and Brett pumps out a lot of amazing content. It’s completely reasonable if he hasn’t read everything Popper has ever written. And if this is the case, no further posts are necessary. Brett can publicly retract his claim, and we can consider this particular dispute resolved, our disagreement here entirely attributable to a small gap in knowledge, which we all have.

It’s either that, or he has read it, and still wants to argue that “you can’t predict human behaviour”. If this is the case, I’ll end this post with a direct challenge to Brett, to be addressed in his response.

Challenge to Brett

How do you reconcile your reading of Popper, i.e that sociological prediction is impossible because of the growth of knowledge, with this quote of Popper’s, which explicitly states that sociological knowledge only grows by the process of (falsifying) sociological predictions?

VM: One example of a “holistic experiment” would be overturning the entire global economic order.

I have two objections against this view: (a) that it overlooks those piecemeal experiments which are fundamental for all social knowledge, pre-scientific as well as scientific; (b) that holistic experiments are unlikely to contribute much to our experimental knowledge; and that they can be called ‘experiments’ only in the sense in which this term is synonymous with an action whose outcome is uncertain, but not in the sense in which this term is used to denote a means of acquiring knowledge, by comparing the results obtained with the results expected. …

VM: “Results expected” is synonymous with “prediction”.

Examples of piecemeal experiments on a somewhat larger scale would be the decision of a monopolist to change the price of his product; the introduction, whether by a private or a public insurance company, of a new type of health or employment insurance; or the introduction of a new sales tax, or of a policy to combat trade cycles. All these experiments are carried out with practical rather than scientific aims in view. Moreover, experiments have been carried out by some large firms with the deliberate aim of increasing their knowledge of the market (in order to increase profits at a later stage, of course) rather than with the aim of increasing their profits immediately.

Poverty of Historicism, p. 71

I’m looking forward to hearing Brett’s response.

(Also, in the quotation you provided Brett, isn’t it interesting that Popper explicitly singles out “economic theories” as his key example of legitimate social prediction?)

Footnotes

-

Or perhaps “quarterly” ejaculator would be more accurate. ↩

-

“Crit-rat” here refers to an online twitter community, and is to be distinguished from “critical rationalism”, Popper’s philosophy. ↩

-

One potential misunderstanding of my previous, and highly critical post on Austrianism, is that I believe the Austrian school has nothing to contribute to our understanding of economics. That isn’t my view at all. AE’s excellent criticisms of Marx’s “labour theory of value” serves as but one (rather obvious) example of AE’s contributions.

What I’m objecting to, and criticizing, is the absolutist attitude that says there is a One True Theory of Economics. Instead, I’m arguing we should simply take the best ideas from all schools of economic thought - for example, Marx’s excellent criticisms of the “child theory of labor”, serving as another example.

But doesn’t Deutsch argue that mixing theories necessarily makes them worse? Yes - but, that’s only a problem for those who consider “the economy” as a single thing requiring a single theory.

I see no reason why that should be the case. I think we need one theory for the optimal way to distribute philanthropic funds to a developing country, say, and another theory (or set of theories) for determining optimal taxation policy. If using data helps us to figure this out, let’s use it. If some random economics undergraduate figures out a clever new technique for analyzing the results of natural experiments, let’s use that too - it matters not which “economic school” this undergraduate came from, provided their technique is sound.

But let’s not a-priori exclude potentially valuable sources of information, from whatever source (logical, metaphysical, empirical), because it doesn’t fit into our framework. Let’s instead expand our framework. ↩

-

“And if they don’t, they they have bigger problems”, a friend remarked. ↩

-

Direct quotes from an anonymous source. Full quote reads:

For example, AE will explain economic regularities through “real” things like actions, preferences, specific prices, the investments in specific (heterogeneous) capital goods (and their specific temporal place in the structure of production) … as opposed to theories attempting to explain the economy via aggregates (stripped from their causal effects) like average price level, level of unemployment, total level of investment.

When I asked if this meant AE rejects using the GPD, as well as related metrics, as measures of progress, growth, etc, the answer was “pretty much yes”. The explanation provided was:

Pretty much yes. Instead of the aggregate output (a single number), they look at malinvestments and where they are located in the structure of production. Malinvestments are investments that would not have been done under a hard money standard where interest rates cannot be artificially lowered. GDP typically goes up under artificially low interest rates (why would you save ?) but creates the malinvestments at the same time that will trigger the recession eventually (combined with hiking of interest rates at some point). Austrians say sustainable growth happens when we first save money (reduce GDP !) so funds and resources can be made available for new, more productive capital goods that will drive GDP back up only later, in line with the temporal preference of consumers for saving/ consuming as expressed by a true market interest rate (not an artificially manipulated one)

-

Note these are not intending to be steelmans of any one particular person’s position, but rather a hyper-generalized amalgamation of a number of different arguments I’ve seen “used in the wild”, so to speak. The hope is that a refutation of these extremely generalized/simplified positions will also serve to refute related/more-specific/more-complex arguments that can be simplified down into this these ones. (Footnote repeated in each section for the skimmers.) ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

See Chapter 8 in C&R, On the Status of Science and of Metaphysics, for a fuller treatment of this subject. ↩

-

They are:

These considerations led me in the winter of 1919–20 to conclusions which I may now reformulate as follows.

- It is easy to obtain confirmations, or verifications, for nearly every theory — if we look for confirmations.

- Confirmations should count only if they are the result of risky predictions; that is to say, if, unenlightened by the theory in question, we should have expected an event which was incompatible with the theory—an event which would have refuted the theory.

- Every ‘good’ scientific theory is a prohibition: it forbids certain things to happen. The more a theory forbids, the better it is.

- A theory which is not refutable by any conceivable event is non-scientific. Irrefutability is not a virtue of a theory (as people often think) but a vice.

- Every genuine test of a theory is an attempt to falsify it, or to refute it. Testability is falsifiability; but there are degrees of testability: some theories are more testable, more exposed to refutation, than others; they take, as it were, greater risks.

- Confirming evidence should not count except when it is the result of a genuine test of the theory; and this means that it can be presented as a serious but unsuccessful attempt to falsify the theory. (I now speak in such cases of ‘corroborating evidence’.)

- Some genuinely testable theories, when found to be false, are still upheld by their admirers—for example by introducing ad hoc some auxiliary assumption, or by re-interpreting the theory ad hoc in such a way that it escapes refutation. Such a procedure is always possible, but it rescues the theory from refutation only at the price of destroying, or at least lowering, its scientific status. (I later described such a rescuing operation as a ‘conventionalist twist’ or a ‘conventionalist stratagem’.)

-

So the above criticisms are only directed towards those Austrians who use this argument to avoid making predictions. ↩

-

One might try to say here that there is a difference between predicting the effects of a policy, which isn’t possible, and evaluating the impacts of the policy after it has been implemented, which is possible. However, this analysis misses that evaluating the impacts of a policy after it’s been implement also relies on prediction, namely it relies on counterfactual prediction of what would have happened if this policy wasn’t implemented. ↩

-

See also Logic of Scientific Discovery, and Realism and the Aim of Science, for fuller treatments of the subjects of probability and statistics, and their role in science. ↩

-

And goes on to say “One of the smartest people I’ve ever met, and also, in certain topics, one of the most dogmatic.” ↩

-

In particular Lectures 9 and 10. ↩

-

Protip: It’s delivered as if he was recording a podcast in 1989, recounting his personal experience working with various people Popper has collided with in writing. Fork up for youtube premium, which allows you listen to youtube while your phone screen is locked, on 2x speed of course, like any other podcast. ↩

-

A few brief comments to make reading easier:

- The book isn’t structured the way I laid it out above. The first two sections are “steelmans” of the historicist position, and last two sections are rebuttals to these steelmans.

- It’s important to recognize what exactly Popper means by “historicism”, and the types of predictions to which his impossibility result applies. I wrote about this in greater detail in my other post, The Poverty of Longtermism.

- Popper uses the terms “anti-naturalistic” and “pro-naturalistic”, which tripped me up when I first read it. By this he means “generally against the methods used by the natural sciences” and “generally in favor of the methods used by the natural sciences.”

- PoH was written at the same time as Open Society, and later sliced up for publication, so a lot of these subjects are given additional treatment in OS, which should be consulted for further exposition on topics such as essentialism, incrementalism, and the nature of scientific prediction.